The first question I asked myself when writing this is why do young people become involved in violence and in carrying weapons?

Violence is a symptom, which from a personal perspective is driven by fear. Fear takes many forms – fear of being a victim, fear of losing face in-front of peers, fear of going home and not knowing what you’ll find there and now more than ever before, drug debt is a huge driver for violence amongst young people even as young as 12.

Young people are using mind altering substances such as cannabis, cocaine, MDMA and ecstasy to cope with life. With next to no income, except perhaps a little saved money from school lunch, in order to fund these drugs young people can find themselves sucked into a life of debt, crime and violence.

The drug dealers are often older than these young people being pushed large amounts of drugs, knowing for sure they won’t be able to pay the debt back. These young people are then faced with few options. Avoid the dealer and hope for the best, again, fear following them everywhere they go.

Unfortunately, their social media accounts are full of messages like “Where’s ma cash?” “If a don’t get ma money by Friday, you’re getting plugged.” This installs additional fear and paranoia in a young person and for their own safety, they think the only option to protect themselves is to leave the house with a weapon or knife.

Many reading this might feel they can surely tell the police, am I right? That the drug dealer would then be taken off our streets, our community would be a better place and the young person would be a safe and a hero? Unfortunately, this isn’t how it works in the life of a teenager caught up in this lifestyle. If they chose this option, the first thing they would be labeled by peers and ‘troops’ would be a “grass” and that they’re not worth anything.

They’d also become vulnerable to people seeking revenge for having “a loose tongue”. Young people also feel if they go and speak to a police officer about a drug debt then they will get into trouble too, the same with speaking to a parent or guardian. That is, if the parents they live with is even capable of helping them with this difficult experience.

Many of the young people I know and have worked with simply don’t have that type of consistent, kind and reliable support available to them in the first place.

So, their only option is to try to deal with the situation themselves. Even children as young as 12 living here in Scotland, are faced with these difficult situations every week. I know first-hand how stressful, scary and exhausting that is and how drugs help with feelings of loneliness, fear, anxiety and terror, which are never far away when living in that environment. The other option could be the young person is now ‘owned’ by the drug dealer and will have to work the debt off by committing crime for the drug dealer. But the truth is the debt is never actually worked off. The young person ends up in a secure unit or a young offenders institute still with a debt attached to their name and so the violence only ever gets worse.

This information is not easy to read and isn’t always easy to understand which is why as a mentor with lived experience of it, I wanted to do something about this terrible situation young people face.

With the backing of the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit, the team at Street & Arrow where I’m a mentor co-created a group work programme aimed at engaging the hardest to reach boys in a community in Glasgow. All united in the belief that things could change for these boys if we were there to help them, the ‘You Decide Programme’ (YDP) was born.

Multi-agency partners were crucial to the success of the programme and included campus Police Officers, local youth workers and housing associations.

Over 8 weeks the team and I worked with boys aged from 12 to 16. We created a space from 5-7pm on a Friday evening where we explored subjects including violence, drugs, alcohol and gangs. These young boys were involved in the criminal justice system and were not attending school or engaging with statutory agencies.

Through this multi-agency approach, the intervention with these lads aimed to re-direct them to a more positive destination. It was unique, as it was co-created and co-facilitated by people with lived experience of the same issues these young boys faced.

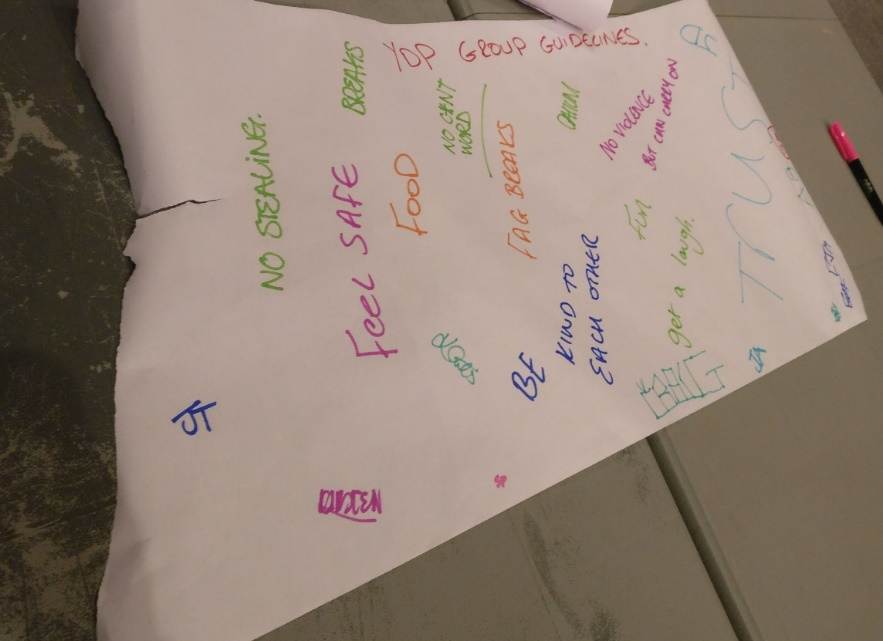

I wanted to share some images of the work we asked the boys to do during sessions. Group guidelines was an activity we did to develop trust and autonomy in the room. The boys decided on the guidelines and everyone participating, signed their name.

A pact; they would be safe in here and their voices heard.

The most important message they got was that we loved them. We believed in them, and they were so much more than the worst thing they had ever done.

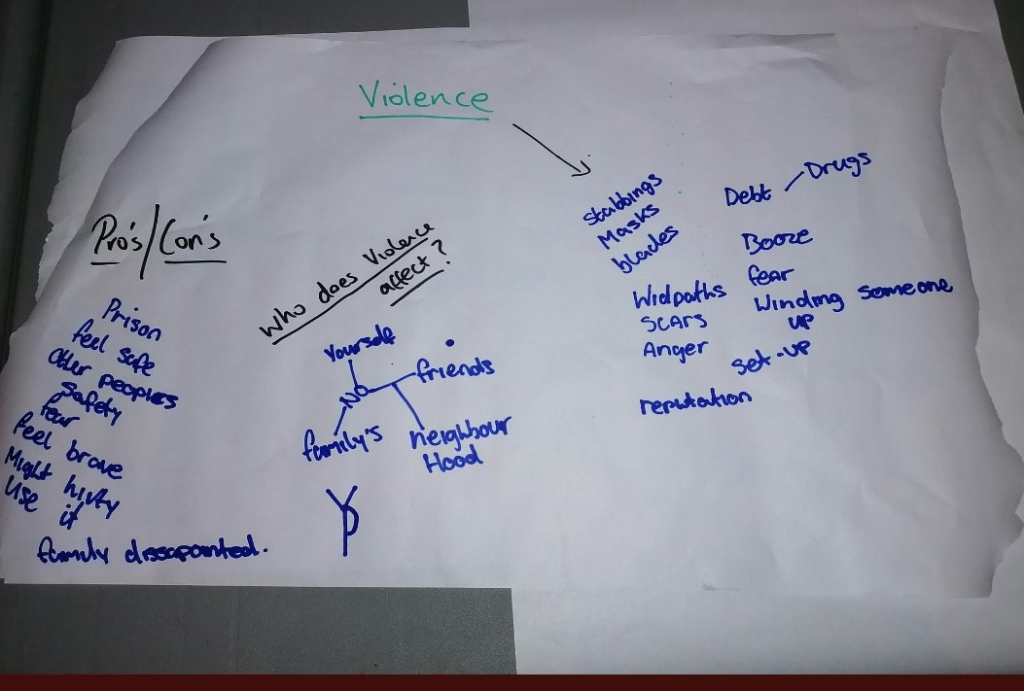

The session on youth violence reinforced that violence is a symptom and is driven by fear and instability. So, did it work?

I believe that if we give young people a voice, and then listen to them to find out why they are using drugs in the first place and that as a society if we understand that drugs lead to violence, then we make progress. Most of them, when asked why they take drugs replied, “I want to get out of my head”. When we asked ourselves the next question “What’s going on in a young person’s head aged 12 where they want to escape it so bad?” we knew the answer was pain.

During the programme sessions, we explored healthy and positive coping mechanisms which included teaching the boys strategies to deal with them not feeling emotionally regulated, because that was exactly the point of the drugs they were taking – they were using them to try to create a solution to cope with and manage life!

A constant theme for these young lads in the group was reminding them that they were so much more than the worst thing they have ever done. We looked to support them to recognize their skills and strengths, and how valuable they are to the future of their community. We also looked to give them a seat at the table on decisions that were being made about their lives and did this by giving them a voice. We wanted to make them feel a part of the solution, because they absolutely are.

When we decided to run this programme, we knew it had to be about their choices – they attended if they wanted to attend, and they engaged with us if they wanted to engage. And guess what? They all did.

There is no truer saying than ‘it takes a village to raise a child’, and if we can imagine a circle of compassion, with nobody standing outside of that circle, then we will be able to care and support our young people much better.

They are not the problem; they are the solution and most importantly they are also our future.